Journals

Three Strategies for the International Spread of Tai Chi

Using Global Open Course Tai Chi Class as an Example

Xiaomin Zhu

Department of Philosophy, Peking University / Research Center for Science Communication, Peking University

In the spring of 2023, I offered traditional Tai Chi classes for the second time in Peking University’s global classroom (two hours per week, one lecture and discussion, and one practical exercise). There were 21 students enrolled, with 20 of them coming from 13 different countries, including 12 from Europe, 5 from the Americas (including 2 from Central and South America), and 3 from Asia. Additionally, a visiting student from Germany attended almost every class and participated in our extracurricular traditional Tai Chi activities as well as Beijing’s garden hiking activities, showing a stronger enthusiasm for learning than the formal enrollees.

Global Open Courses Spring 2023 Tai Chi Course Poster

From classroom teaching and discussions, interactive exchanges in the class WeChat group, participation in extracurricular Tai Chi and hiking activities, to the final 5-minute student presentations and feedback on the course content, the learning outcomes and individual gains of everyone have greatly exceeded our expectations. For example, through a semester of learning and practicing Tai Chi (with a requirement for everyone to practice at least 20 minutes a day), most students who were encountering Tai Chi for the first time were pleasantly surprised to discover that: either their long-distance running performance had improved, or their weightlifting ability had increased, or their swimming technique had significantly improved, or their skills in tennis and golf had noticeably advanced. Other common improvements included significant relief from back pain, the disappearance of recurring muscle injuries, and improvements in insomnia and reduced stress.

To be honest, even I find it difficult to imagine that Tai Chi could have such a remarkable positive impact in so many areas. It’s almost as if “a blank canvas can create the best and most beautiful paintings” or as if “foreigners taking traditional Chinese medicine enjoy great outcomes.” Undoubtedly, this also demonstrates that our traditional Tai Chi has its unique cultural charm and significant practical value, opening a new and magical window for foreign students to discover themselves, experience China, and view the world.

In light of this, summarizing the three fundamental approaches that our course has gradually developed in the international exchange of Tai Chi practice is undoubtedly meaningful. These three approaches are: 1. Harmony in Diversity: Returning to the paradigm of traditional Tai Chi; 2. Practical Insight: Realizing the Dao/Ways through the Body; 3. Civilizational Exchange: Sharing Beauty Together. In fact, these three are interconnected, mutually reinforcing, and mutually affirming. For instance, by better understanding the paradigm of traditional Tai Chi through the perspective of civilizational exchange and comparison, and by deeply experiencing the uniqueness of traditional Tai Chi and the similarities and differences with other cultures through multi-layered practices such as individual practice and social observation.

Practice in Class

Harmony in Diversity: Returning to the Paradigm of Traditional Tai Chi

A core idea of our course, “Traditional Taijiquan: Different Philosophy and Practice,” is to express Tai Chi as traditionally as possible. Especially in a society where Western science serves as the standard for judgment and Western sports are prevalent, effectively disseminating traditional Tai Chi requires a paradigm shift. Of course, we do not reject or deny the power of modern science, which is a specialized discipline, and the pursuit of higher, faster, and stronger in Western sports when studying and exploring Tai Chi. For example, we also use some modern scientific concepts to help people understand Tai Chi. I often describe the state of Tai Chi as “hydraulic machinery,” where the body responds inside and out, coordinating all around, and maintaining a state of unceasing motion. Many learners find this description very apt. Furthermore, traditional sayings such as “practice Tai Chi within the area occupied by a resting ox”, or “within the space of a single mat” may not be readily understood by young people today. Our approach of “one minute of practicing Tai Chi”, “one square meter for Tai Chi practice” has a similar effect and is very well received by everyone.

Golden Pheasant Standing on one leg in the classroom

Pioneering Chinese sociologist Fei Xiaotong pointed out, “In the process of maintaining contact and active exchange with the Western world, we should turn our good things into global goods. It begins with localization and then globalization.” Tai Chi has aspects that cannot be explained by Western science, or that Western science is unwilling to explain, only partially understood, or may be intentionally or unintentionally overlooked. We are highly vigilant about the potential negative consequences that may arise from this. Traditional Tai Chi has its unique concepts of understanding and practicing, and many traditional modes of understanding and practice have long been ignored or even distorted by modern research, teaching, and sport competitions. Therefore, we hope to restore, to some extent, an understanding and perception of the localization and traditional mode of Tai Chi. In this sense, especially in a situation where modern science monopolizes discourse, returning to the traditional paradigm can also be considered as “continuing the holy but interrupted tradition.” For this reason, one basic approach of this course is to return to the paradigm of traditional Tai Chi, to present and express it. In the first class, I ask everyone to temporarily set aside some so-called objective, scientific, logical judgment standards. I encourage everyone to fully feel, understand and appreciate Tai Chi without any preconceptions.

It can be imagined that foreign students, who are essentially beginners, initially find some of the traditional and novel concepts of Tai Chi difficult to accept and identify with. They may even find it bewildering, but this often easily sparks strong interest and lively discussions. Due to space limitations, from the students’ learning and feedback, or rather from the dialogue between Chinese and Western cultures, we have selected the following three main viewpoints that have generated more interactive exchanges in the class for discussion.

First, Tai Chi basically lacks objective and uniform standards. “Ten people, ten Tai Chi.” Many students initially raised questions, expressing their inability to understand: with no standards, how can one learn Tai Chi well or consider themselves to have learned it well? In response, we specifically introduce the different philosophies and practice methods of various traditional Tai Chi schools. Some of these philosophies and methods may conflict or negate each other. Everyone can choose based on their own practice insights and personal preferences. There’s no right or wrong, no high or low in this matter; everyone can make their own choices and can select the philosophies and movements of any school for practice. I also use the saying from Qi Baishi who’s a great painter, “Those who study me live, those who imitate me die,” to warn everyone: if your movements become more like mine, they may restrict you, possibly affecting your correct understanding of movements. On the one hand, “Tai Chi is essentially one family,” and on the other hand, “Do as you wish within bounds.” Gradually, everyone came to like this philosophy.

The feeling in Tai Chi is very important, as “internally, it cultivates the spirit; externally, it demonstrates tranquility.” However, this feeling cannot be subject to uniform, objective standards. Additionally, certain feelings may occur only once and are difficult to reproduce. It presents a constant state of flowing and shifting, an always changing form at all times, much like Chinese philosopher Wang Yangming’s saying, “Movement becomes energy, concentration becomes essence, subtle application becomes spirit.” Foreign students often ask Tai Chi masters, “What is the specific route for the thought process from here to there?” The master responds, “There is no fixed route; it’s never the same every time.” A student from Singapore expressed, “If Tai Chi enters the Olympics, it does indeed face a paradigm shift. How can you judge and score Tai Chi, an art where each person has their own Tai Chi? Furthermore, this art pursues individual cultivation and practice rather than competitive performance.” She said she would continue to pay attention to this issue and hopes to find a solution to the dilemma in the future.

Secondly, a key principle of practicing Tai Chi is to find comfort. A Wu-style Tai Chi master taught his disciples, “When practicing Tai Chi, every cell should be joyful.” Being comfortable indicates that you are doing the movement correctly; there is no need to compare your form with others. Many traditional masters refuse to participate in or judge some modern standardized and predefined Tai Chi competitions. They believe, “Tai Chi itself is not suitable for competitions.” There is a tale in the cobmmunity about a renowned Tai Chi master who brought his disciples to competition, and his disciples all received awards, but the master himself, who was well-known and respected in various circles, failed to gain recognition. Formerly one of Beijing’s “Tai Chi Five Tigers,” Li Jingwu said that Tai Chi Kung Fu is practiced for oneself, not for others to watch. Yang-style Tai Chi master Wang Yongquan also mentioned that the best state for practicing Tai Chi is when no one is watching—because when someone observes, it is difficult to avoid performing with the intention of winning.

Three students from El Salvador, Malaysia, and Italy practice Tai Chi together with Kung Fu Panda Po

Once again, internal energy and the concept of the energy field remain topics of great interest and discussion for everyone. Cheng Man-ching pointed out that there are three types of energy in the human body: the breath, the blood energy, and the primal energy. He believed that Tai Chi's internal energy should be the human's primal energy, but he did not provide a clear explanation of what primal energy is. Different branches of traditional Tai Chi have varying views on this, some praising it highly, some being ambiguous, some mysterious, and some entirely rejecting it. In the face of these ambiguous, conflicting, or opposing concepts, we suggest that everyone should set aside disputes and participate together. There's no need to rush to achieve a so-called rational, scientific definition or a forced generalization. “Elusive and vague, yet it resembles something.”(by Lao Tzu ) You might as well experience and deeply feel it with an undifferentiated mind during the practice. At the same time, do not grasp or resist during the practice; let it flow naturally.

Of course, we will also provide some previous experiences for reference. For example, masters of Yang style of Tai Chi Li Yaxuan and Dong Yingjie both mentioned that during Tai Chi practice, having warm or hot soles of the feet is correct. We teach and guide students to feel whether the palms or soles of their feet are getting warm when performing the movements. Many students feel warmth in their palms while doing the movements. A few students even feel warmth in the soles of their feet (though I suspect that this might be influenced by psychological suggestions, as warmth in the soles of the feet is relatively rare). Many students mentioned in their assignments that they occasionally feel warmth in their feet during practice. Although it's an occasional feeling, the unprecedented bodily sensations brought by Tai Chi have already made them feel amazed and pleasantly surprised.

One Tai Chi practitioner (by the way, he has a master's degree in liberal arts from a prestigious Beijing university) told me: “After practicing Tai Chi and energy release every day, he expels black substances through the soles of his feet using internal energy. Now, he has a rosy complexion and a radiant spirit, all because toxins have been expelled from his body.” I listened with a mix of belief and skepticism. I specifically inquired about this detoxification phenomenon from the traditional Tai Chi masters of various schools. Most of them almost disdainfully dismissed his words, and some even ridiculed, “This young man probably forgot to wash his feet, right?” For these different individual phenomena, opposing viewpoints, and various reactions, we try to present them to everyone in a comprehensive, authentic, and full manner. We organize classroom discussions while emphasizing that there is no unified, scientific standard answer. Everyone's bodily reactions after learning Tai Chi are likely to be different, and students can refer to and discuss others' experiences while making their own judgments.

Regarding the energy field, there is a Chinese folk tale about four mythical creatures that can sense people's energy and inner martial arts. These creatures are the fox, snake, yellow weasel, and hedgehog, and they will be attracted to practitioners. I shared my own experiences of encountering hedgehogs three times, which sparked a great deal of interest among many students. Some expressed hopes that they would also attract small animals while practicing Tai Chi.

The first time, it was near a pond by my office where I often practiced Tai Chi at night. I would usually see hedgehogs moving around in the surrounding bushes. Sometimes they even came quite close. One evening, as I was repeatedly performing cloud hand, I suddenly felt something near my feet. When I looked down, a hedgehog's mouth was already touching the bottom of my trouser leg. I was startled and quickly stomped my feet to scare it away. I don't dislike hedgehogs; I was just concerned that I might need to deal with complications like vaccinations if I were bitten.

The second time was during the pandemic when I would often practice Tai Chi alone at night near the eastern gate of the Old Summer Palace. At the time, there was still a wire fence outside the wall. I saw a yellow weasel directly climb up the straight wall and enter the park. I also frequently saw hedgehogs, moving back and forth along the base of the wall in the bushes. One night, I was practicing Tai Chi in a dimly lit area along the wire fence. There was no one around. A hedgehog approached from the other side of the fence and came within about 30 centimeters of me. It stood there quietly for a full 5 minutes (as if it knew that we were both safe on either side of the wire fence). I took out my phone to capture a photo, but unfortunately, the streetlight was dim, and the image was quite blurry.

The third time, I was practicing Tai Chi on an open field near the Weiming Lake on campus at night. A hedgehog approached twice, running from under a large tree towards me both times. When it got to about 20 centimeters from me, I stomped my feet to scare it away each time.

The Tai Chi postures of the three students from France, Germany, and Singapore while strolling in the park

During classroom discussions, I emphasized that such occurrences are almost impossible to predict. I've been practicing Tai Chi for over a decade, doing it practically every day, accumulating well over 4,000 sessions. However, I've had the experience of attracting hedgehogs as described above only three times. Strictly speaking, even in these three instances, there are many possibilities to consider: these hedgehogs might have been sleepwalking or simply lost their way, stumbling upon me by accident. From a statistical perspective, a 3:4000 ratio might seem insignificant, but can we deny the authenticity of these three experiences based on this alone? Can we completely dismiss the existence of an energy field?

Chinese traditional Tai Chi has many unique situations and bodily sensations that are hard to replicate, unpredictable, and impossible to test repeatedly. If we try to understand or explain these experiences solely from a scientific, quantitative, objective, testable, repetitive perspective, we might never truly grasp the traditional paradigm of Tai Chi. Most of the students expressed their understanding and agreement, hoping to learn and understand Tai Chi in the traditional way.

Practical Insights: Realizing the Dao through the Body

As “the Dao must be embodied before it can be understood,” from the beginning of the course, I made it clear that in addition to literature readings and classroom discussions, practicing Tai Chi is essential. I required everyone to practice for at least 20 minutes each day and encouraged them to observe the real-life situations of Tai Chi in Chinese society while visiting various parks or traveling. It should be noted that the enthusiasm for practice was very high, and everyone appreciated the idea of practicing Tai Chi for one minute, even in a one-square-meter space. For example, a French student practiced the Golden Pheasant Standing on One Leg while riding the subway, and she found that the Beijing subway was much smoother than the ones she had experienced in France. This allowed her to conveniently use her commuting time to practice Tai Chi movements. Many students shared their practice pictures and observations of Tai Chi activities from various places in the course's WeChat group. They also realized the role of Tai Chi as a social bond that enhances the mutual feelings among practitioners.

Some students practiced a few Tai Chi movements while climbing the mountain path of the Great Wall. Some sent pictures of local university students performing Tai Chi in Gansu, posing in Tai Chi shapes with famous landmarks in the background. Others observed the elderly practicing Tai Chi at the Chengde Mountain Resort. A few students saw a Tai Chi animation video being played in the art exhibition area in Shanghai, and they shared it with the class. This video led to a dedicated discussion in class, as students noticed that the Tai Chi movements in the animation were mainly isolated limb exercises, lacking the fluidity, harmony, and holistic essence of traditional Tai Chi.

I took foreign students to the Yang-style Tai Chi practice area in Beijing Yuan Dynasty Relic Park twice to experience traditional Tai Chi. I asked a highly skilled local Tai Chi master to explain Tai Chi to the foreign students. However, both times, he flatly refused without negotiation. I had to explain to the foreign students that some people refer to Tai Chi as a “acquaintance culture.” Typically, practitioners don't easily engage in conversations or push hands with strangers. To interact more deeply with these traditional masters, you need to become friends with them first, and then they will be more willing to engage with you. I believe this cultural aspect of Tai Chi can help foreign students better understand the ecological conditions of traditional Tai Chi in contemporary Chinese society and gain a more specific understanding of how “tradition often remains with those not affected by modern education.”

The Singaporean student practiced Tai Chi cloud hand during her conference in Nanning.

L, who has been passionate about swimming since childhood and regularly represented her school in swimming competitions, continued her swim training at Peking University with four sessions per week. However, she struggled with mastering the technically complex butterfly stroke. Either her arm movements left her breathless, her muscles fatigued prematurely, or her technique remained imperfect. At times, she even doubted if the butterfly stroke was “all seemed to demand more than I could give.” After practicing Tai Chi for nearly three months, she noticed significant improvements in her strength, flexibility, and balance. She vividly recalls that in mid-May, during a routine practice, she effortlessly completed a 50-meter standard swimming lane using the butterfly stroke. She was amazed at her synchronized arm movements and the considerable improvement in her butterfly stroke technique. Her endurance had also significantly improved. She attributed these achievements to her daily Tai Chi practice, believing that it was “not only benefiting my physical and mental health but were also directly contributing to enhancing my swimming skills.”

Dutch student F is a dedicated long-distance runner, having reached the summits of 7000-meter mountains and frequently participating in various running competitions, including two full marathons. However, in a running training session in 2021, he suffered a severe thigh tendon injury, leaving him unable to walk for over two months. Even after treatment, his thigh tendon continued to cause him discomfort, with occasional relapses triggered by minor accidents, such as stepping on small stones. This was a significant blow to his running aspirations, leading him to pessimistically believe that his dreams were shattered. Since the beginning of this semester, through daily Tai Chi practice, he happily discovered that his previous thigh tendon injury never recurred. He found that the cloud hand movement, sitting back on his haunches, was particularly effective in stretching his thigh tendons. Furthermore, he experienced a “harmonious flow” within his body, truly understanding the marvelous aspect of Tai Chi: the “use intention, not force” principle. During his practice, he felt warmth in both his hands and feet, strengthening his unwavering belief in Tai Chi's ability to awaken internal energy. On May 5, 2023, F participated in Peking University's 5.4-kilometer run from the Peking University campus to the Old Summer Palace as part of the May 4th Youth Day celebrations. He rekindled his passion for long-distance running and, based on his personal experiences, deeply recognized the practical value of Tai Chi in preventing and reducing running-related injuries. He made a sincere recommendation: “Every marathon runner to perform at least half an hour of Taijiquan practice every day, which allows for creating unity between body and mind.”

Students from the Netherlands and Mexico practiced Tai Chi by the side of Peking University's Weiming Lake

Of course, our practice had some lessons to be learned. “Squatting before the Wall” (also known as “the first skill of Chinese martial arts”) was playfully referred to as the pinnacle of Chinese martial arts, emphasizing the coordination and unity of the whole body, allowing people to experience the feeling of internal and external harmony and overall force in Tai Chi. A German student mentioned that Squatting before the Wall allowed her to experience for the first time the importance of willingness in controlling the body and movements.

Therefore, we included Squatting before the Wall as a fundamental exercise in Tai Chi, with each session requiring each person to perform it at least three times. In the beginning, most students found it exceptionally challenging, struggling to maintain their posture and facing various issues. For example, the movement required them to face the wall, flatten both arms, touch the wall with the tips of their toes, and then squat down and stand up without touching wall by nose or hands. However, everyone exhibited their unique skills, with some tilting their heads backward, some turning their faces to the side, and then pressing the other side against the wall (because as foreigners, they complained about their noses being higher, feeling somewhat disadvantaged), and others scratching the wall with their fingers. A Dutch student who’s worrying his rigid body unsuitable to practice Squatting before the Wall specially talked to me once time: “The Squatting before the Wall is designed by Chinese masters for Chinese people, as a result, is it inappropriate for us Europeans to do this movement considering it’s difficult for us even doing Asian Squat?” However, a slim and agile Italian male student mastered it within a month, impressively performing a variety of moves during each practice session, and boldly calling himself the “Squatting King” in our class's WeChat group. This likely dispelled many of the worries of the Dutch student, and, finally, at the beginning of June—during our last practice session, he completed Squatting before the Wall with an overwhelming sense of achievement and ceremony.

Author's Classroom Teaching Practice: Divide Right Foot

In our class, there was a tall and relatively overweight student who initially showed a lot of enthusiasm and seriousness at the beginning of the school year. In one class, he expressed his fear of falling while attempting the wall squat exercise and hesitated to squat down. I reassured him that he could start without touching the wall with his toes and take it slow. I told him that with practice, he should be able to overcome his fear. I remember that during one of our hikes in Old Summer Palace, he also mentioned that he was afraid of climbing mountains and falling. This indicated that he had relatively poor balance and coordination. Perhaps I didn't pay enough attention to his difficulties and concerns, and this student seemed to lose interest later on and didn’t come to class very often. In his assignments, he expressed his disappointment at not being able to complete the wall squat exercise, which was also a regret for me.

Similar situations were also common in our extracurricular traditional Tai Chi activities. Some people would show an immediate passion for Tai Chi when they first joined, and their initial experiences with the practice would be quite satisfying. It's often said, “Excellence requires talent, greatness requires passion.” I even began to wonder if I had encountered some Tai Chi “chosen ones.” However, these enthusiastic learners tended to lose interest quickly, often attending classes with great dedication for only a couple of sessions before disappearing without a trace. This sometimes led me to feelings of confusion and self-reflection: to be or not to be—was this my problem or theirs?

In August 2023, a student went back to his country for the summer and taught his parents how to do the wall squat exercise at home. He even sent a photo and expressed amazement that his dad and mom were doing it better than him. In the photo, both of his parents were standing with their faces to the wall, their feet parallel and shoulder-width apart, and their toes touching the wall. They were squatting down correctly, but there were two cushions on the floor behind his father, presumably to prevent him from falling in case he lost balance. This inspired us to provide cushions for those international students in the class who may have poor flexibility and coordination (Chinese students and other Asian students often have a relative advantage in this regard, so we sometimes find it hard to understand the unique physical and psychological challenges that European and American students face when doing this exercise). This can be considered an example of cross-cultural exchange and mutual benefit.

Two female students from Singapore and Malaysia both had a background in dancing since childhood, and they were among the very few students in the class who could touch their elbows to their toes

Cultural Exchange: Sharing Beauty Together

The renowned Indian poet and the first Asian Nobel laureate in Literature, Rabindranath Tagore, strongly opposed the concept of “comparative literature” and the notions of superiority or inferiority that it implies. He offered an alternative concept of “world literature”, emphasizing that the literature of every nation is a rich member of the global literary family. Each one is beautiful in its own way, and through cross- reference and an inclusive mindset, they can all contribute collectively. Similarly, the international spread of Tai Chi is not about comparisons, judgments, or determining who's superior or inferior. Instead, it's about showcasing oneself in the modern, diverse, and interactive world, expressing one's unique identity and offering a wide range of choices to the world. International students from diverse cultural backgrounds continually reveal new perspectives and pathways for the propagation of Tai Chi, greatly expanding its horizons and prospects.

British student Y was the only one in the class who wrote his final paper in Chinese and even had a Chinese friend help proofread it. Y was skilled in playing the cello and learned to play the erhu, a Chinese musical instrument, during his time at Peking University. His paper's title was “Tai Chi and Western Classical Music,” where he discovered that the principles of Tai Chi, such as nature, flow, harmony, and wholeness, were also reflected in Western classical music composition and improvisation. He was pleasantly surprised to find so many similarities between the two, and he noted that no one had explored this connection before. As possibly the first person to delve into the topic of Tai Chi and Western classical music, Y hoped for further research in this area.

While hiking in Old Summer Palace, the author and students took the opportunity to practice Tai Chi on a boat, experiencing the sensation of moving like water

Canadian student R adopted a dog seven years ago to serve as a guard dog at home. Over time, the once-small puppy has grown into a robust 120-pound (over 54 kg) dog. R's new concern was that she could no longer control a dog that was stronger than her. Especially when the dog enthusiastically jumped at her or pulled her unexpectedly, she felt helpless and even feared losing her balance and getting injured. To address this issue, she consulted relevant literature and learned that it was a common problem for people with large dogs. This semester's Tai Chi class provided her with a refreshing solution. Her paper was titled “Tai Chi and Dogs.” R believed that some Tai Chi principles, e.g. “Following the trend of others and borrowing their strength”, especially those from Tai Chi Push Hands exercises, could be applied to control and guide her own dog. Techniques such as the reverse roll of the arms in Wu/Hao style Tai Chi, which allows one to act as a rotating gate, always ready to unload any force coming from any direction, were particularly intriguing to her. With newfound confidence, she was eager to apply these concepts and techniques when she went home for the summer to practice with her dog.

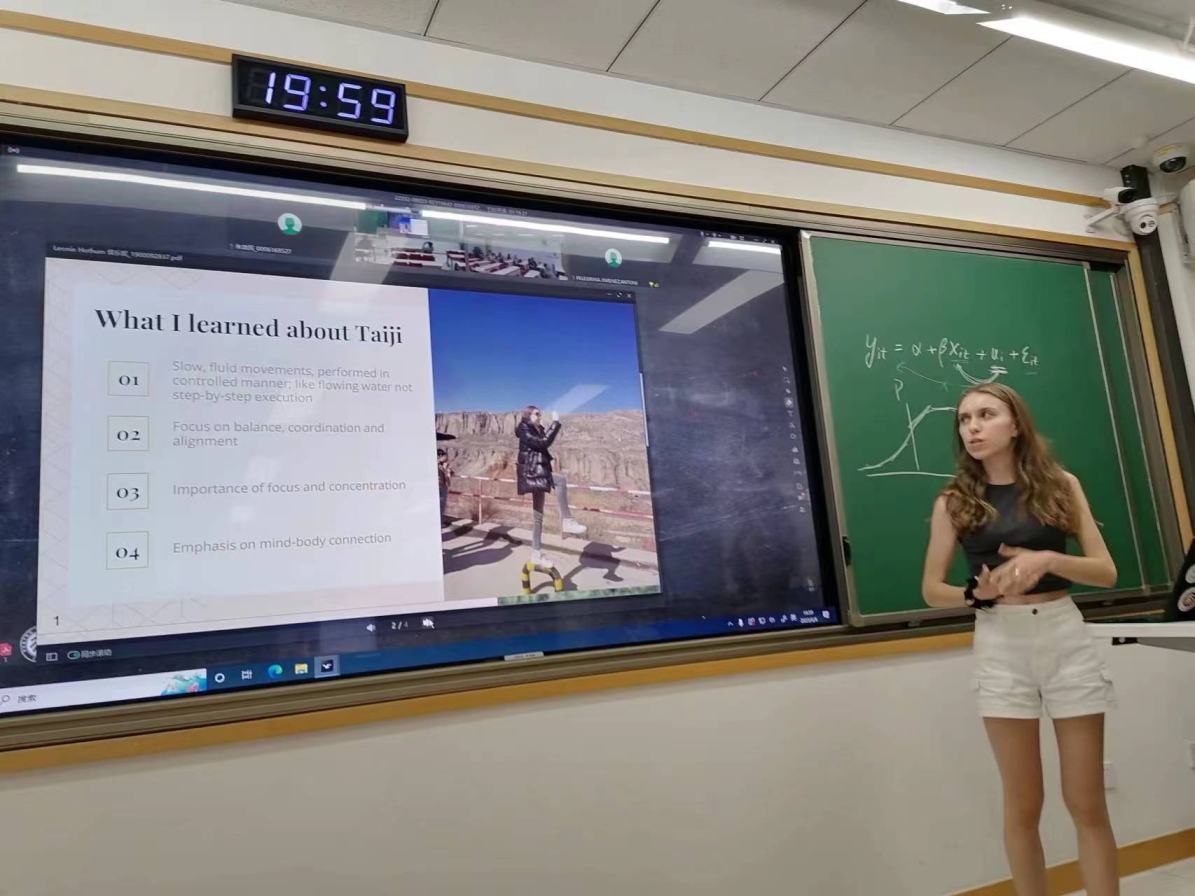

During the course summary presentation, the German student showcased her Gold Pheasant Standing on One Leg that she had practiced in a scenic area in Gansu province, China. Her presentation outline revealed her deep understanding of Tai Chi principles

As for the French student, J, she had been suffering from chronic back pain for a long time and had tried various medical treatments like physiotherapy and acupuncture with unsatisfactory results. Additionally, she had been doing weightlifting to increase her back muscle strength. However, it was during the Tai Chi class that she unexpectedly found the “Squatting before the Wall” movement, to be exceptionally effective in alleviating her back pain. This particular Tai Chi move became her favorite, further igniting her interest in practicing Tai Chi. J is now delighted to believe that she has discovered a solution for her back pain, which involves combining weightlifting's muscle strength training with Tai Chi's overall coordination, resulting in a harmonious blend of Eastern and Western influences, where Yin and Yang are balanced, and she finds her own path to well-being.

Several students who had experience with yoga, meditation, and mindfulness found remarkable similarities among these Eastern health and wellness practices. They spontaneously recognized Tai Chi as a “moving meditation.” They saw how the combination of motion and stillness, relaxation without slackness, and the integration of inner and outer elements created a profound new experience. These students realized that many health and wellness approaches from different cultures had commonalities, allowing them to complement and enrich each other.

There is an interesting anecdote when we practice pushing hands (a Tai Chi practice). According to the past experiences of domestic students in push hands, in the practice of "Double Push Palms" (where two students stand facing each other and making contact only with their palms, they push each other and one loses if his any foot moves), we initially had male students stand on one leg while female students engaged in pushing. However, when I myself tried to stand on one leg and engage in push hands with some foreign female students, I found it challenging to locate their body's stiffness points. Instead, I felt a bit off-balance. Later, I discovered that many foreign female students had extensive backgrounds in activities such as yoga, dance, gymnastics, or ballet since childhood. As a result, their bodies were generally more flexible and coordinated. It was a case of "you don't know until you try." We quickly abandoned the requirement for male students to stand on one leg for push hands. Even so, there were still occasions when petite female students, by applying Tai Chi principles, managed to displace taller male students in push hands (most foreign male students, although taller and stronger, often had stiffer bodies and were more prone to losing balance with slight adjustments). This made the female students even more excited and emotionally charged, becoming the highlights of the class.

During practical lessons, when I asked everyone to choose their favorite move for collective practice, it was surprising how many times female students voluntarily suggested participating in push-hands with male students. Tai Chi, with its principles of using the small to defeat the large, softness overcoming hardness, and weakness prevailing over strength – what many students consider "unbelievable" and "magical" principles, found their concrete realization and perfect presentation in this hands-on practice.

It is said that the cross is a symbol of Western Christianity, the crescent moon is a symbol of Middle Eastern Islam, and the Tai Chi yin-yang symbol is increasingly recognized as a symbol of Chinese civilization. The philosophy of Tai Chi has continuously thrived throughout the long history of China and remains vibrant today. Its unique concepts have enduring significance in the contemporary world and offer practical value. Tai Chi's appeal transcends cultural backgrounds and captivates students from around the world. German student H had studied karate for 12 years before beginning Tai Chi, and he discovered several similarities between the two practices. He believed that Tai Chi taught the principles of keeping the body supple and linking various techniques with fluidity. I will now use the final paragraph of his term paper as the conclusion of this paper:

“After a longer period of no training, picking up Tai Chi ignited my initial interest and I could feel a little like six-year-old self, standing in a martial arts school and being fascinated by the masters techniques”

Xiaomin Zhu, Three Strategies for the International Spread of Tai Chi:Using Global Open Course Tai Chi Class as an Example, Shaolin and Tai Chi, 2023:09, pp7-17

Translated by: Wu Tianpeng